My fellow avant guardian, Ari, asked a fine question in the comments to my popOp post this week and below is my response (it's the same response I've posted on the avant guardian):

This video embedded in my post got me thinking about what Hannah Arendt said, “There exists in our society a widespread fear that has nothing to do with the biblical ‘Judge not, that ye be not judged,’ and if this fear speaks in terms of ‘casting the first stone,’ it takes this word in vain. For behind the unwillingness to judge lurks the suspicion that no one is a free agent, and hence the doubt that anyone is responsible or could be expected to answer for what he has done.” (emphasis mine)

And this is precisely the point of discussing spectacular agency.

If you noticed (I didn’t until the second go round) toward the end of the clip (around the 8th minute, I think) you can clearly see the cops have a guy standing on the other side of the human wall with a video camera.

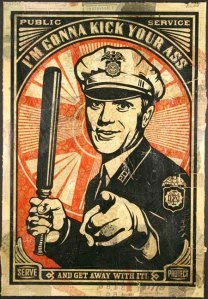

Since Rodney King it’s been very clear to folks that want to rage against the machine that having video images of brutality will work in your favor as the spectacle of violence usually communicates something rapidly (usually it’s a moral claim akin to “we’re David and they’re Goliath, Help!”) Among military circles there’s been this discussion for about ten years that the Pentagon needs to learn the lessons of “public diplomacy” and usually they’ll point-out that Al Qaeda-like networks are successful at recruiting and sustaining fighting against the largest military of all human history because they have the ability to win moral arguments using simple strategies like showing people getting killed by the outsider. Public diplomats point out that these videos are damaging because they reduce the (U.S.) mission to simple images of Goliath smothering Davids. So, they say, the Pentagon should find ways to reduce their enemy combatants to images as well.

This is why the Toronto police are armed not only with massive military force, they are also armed with mass communications force. They are out there reducing their enemies to images. Then, were a trial to be called, the police would have their images fight the images brought forward by the protesters. Thus I talk about spectacular agency: what kind of agency do you have when you’re reduced to such?

Ultimately, I believe that the frustration I feel is not that the protesters were not thinking, I suspect they thought this was a legal, non-offensive, active in my democracy-type action. They ask the riot police where they should go, they plead with them, as human beings to communicate. These people want to be compliant with the physical demands of the police and the police don’t allow that. The police, probably acting on the orders from someone not able to see what is happening in the situation, respond with beatings and arrests and detention.

The trial of Johannes Mehserle (this cop stands accused of murdering Oscar Grant III, which he claims was an accident and only meant to use his Taser on Grant, even though he clearly uses the gun in the manner he’s been trained and is completely unlike the way one fires a Taser) raises a similar issue. The law is such that if a cop feels endangered, the cop can use lethal force at their discretion. Thus it’s legally very difficult to establish whether it is excessive to shoot in the back and kill a man who is prone on his stomach, hands under his body. Legally it’s tough to establish that.

But morally it’s clear that Mehserle was wrong to do that. Even if it was the case that he meant to use his Taser, Mehserle only establishes with that fact that he is guilty of manslaughter and criminal negligence. But legally it’s unclear. I say he should be judged.

Judging, like improvisation, as you brought up, is a risk that must be taken.

Showing posts with label Hannah Arendt. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Hannah Arendt. Show all posts

Saturday, July 3, 2010

Friday, June 11, 2010

New Post at the avant guardian

This week on popOp we look at doctors performing experiments on the recipients of torture from the U.S. government (you're welcome, torture victims, I'm sure you find solace in knowing that future victims will have a more effective and efficient mode delivered to them). How would Hannah Arendt think about it, would it look anything like what Confucius taught?

Things that make you go hmmm.

popOp!

Things that make you go hmmm.

popOp!

Monday, November 9, 2009

Heidegger & Arendt in the Popular Media

My dear friend, John at the University of Hawai`i Mānoa, shared this link to a New York Times article introducing a new book on Heidegger.

In this article, by Patricia Cohen, I am once again reminded why it is important that at all times I strive for comprehension by those that hear me. Cohen's article promulgates several unfortunate and familiar - as in cliche - opinions (not hers, I suspect, but present without discussion) about Heidegger, Hannah Arendt, and ultimately thinking itself.

The article, it seems, exists to inform the Times' readership that Emmanuel Faye's book is going to be published soon. I s'pose we must consider it, then, an advertisement. But Cohen's article seems largely to be infotainment as what is reported here is that there is (cue the E! and Inside Edition people) a scandal at play in this publication! OMG! Heidegger had sex with Hannah Arendt! Quick! Get the editors on the horn, we got us a whopper!

(now an imaginary conversation in my head)

Editors: Good eye, Cohen. But this is the New York Times, we're really more a vehicle for advertising on the backs of information. You gotta present more information here. Did anyone else announce that this book was going to be published?

Cohen: Yes, the Chronicle Review

Editors: Great, now it looks like we did some background work. Run it. Remember, "if it bleeds, it leads."

Sorry a flight of fancy. I suppose I should remember that the Books section of the NYT is simply an advertisement.

But is that all it should be?

Couldn't the paper present something more?

I'd just like to point out one thing that seems glaringly obvious, but probably would upset those whose palms were greased in getting this infotainment manufactured: the gist of the book is that Heidegger thought one way and acted in other ways, and the author (Emmanuel Faye) doesn't like that.

Faye doesn't like that there is this ambiguity (adults, I sugges,t are marked by their ability to navigate ambiguity).

Now, it might seem unfair to do this, but didn't Heidegger himself say that we cannot overcome previous thinkers by simply dismissing them, we must think what was unthought in our predecessors? In other words, what ever philosophy is, what ever thinking is, it is first and foremost a task that requires thinking/philosophizing with those that came before us. It's an activity that requires considered opinion. It's a task (when done properly) that will be reminiscent of deep affection or love: philosophy = love (philia) of wisdom (sophia).

True to the tabloid nature of mainstream media, Cohen brings in Hannah Arendt (the Rihanna to Heidegger's Chris Brown) simply to say that Heidegger tainted her thinking and cites another unfortunate piece by Ron Rosenbaum at slate.com. Rosenbaum, naturally, parades the familiar (again, cliché) idea that Arendt's phrase "the banality of evil" is too dismissive.

In this article, by Patricia Cohen, I am once again reminded why it is important that at all times I strive for comprehension by those that hear me. Cohen's article promulgates several unfortunate and familiar - as in cliche - opinions (not hers, I suspect, but present without discussion) about Heidegger, Hannah Arendt, and ultimately thinking itself.

The article, it seems, exists to inform the Times' readership that Emmanuel Faye's book is going to be published soon. I s'pose we must consider it, then, an advertisement. But Cohen's article seems largely to be infotainment as what is reported here is that there is (cue the E! and Inside Edition people) a scandal at play in this publication! OMG! Heidegger had sex with Hannah Arendt! Quick! Get the editors on the horn, we got us a whopper!

(now an imaginary conversation in my head)

Editors: Good eye, Cohen. But this is the New York Times, we're really more a vehicle for advertising on the backs of information. You gotta present more information here. Did anyone else announce that this book was going to be published?

Cohen: Yes, the Chronicle Review

Editors: Great, now it looks like we did some background work. Run it. Remember, "if it bleeds, it leads."

Sorry a flight of fancy. I suppose I should remember that the Books section of the NYT is simply an advertisement.

But is that all it should be?

Couldn't the paper present something more?

I'd just like to point out one thing that seems glaringly obvious, but probably would upset those whose palms were greased in getting this infotainment manufactured: the gist of the book is that Heidegger thought one way and acted in other ways, and the author (Emmanuel Faye) doesn't like that.

Faye doesn't like that there is this ambiguity (adults, I sugges,t are marked by their ability to navigate ambiguity).

Now, it might seem unfair to do this, but didn't Heidegger himself say that we cannot overcome previous thinkers by simply dismissing them, we must think what was unthought in our predecessors? In other words, what ever philosophy is, what ever thinking is, it is first and foremost a task that requires thinking/philosophizing with those that came before us. It's an activity that requires considered opinion. It's a task (when done properly) that will be reminiscent of deep affection or love: philosophy = love (philia) of wisdom (sophia).

True to the tabloid nature of mainstream media, Cohen brings in Hannah Arendt (the Rihanna to Heidegger's Chris Brown) simply to say that Heidegger tainted her thinking and cites another unfortunate piece by Ron Rosenbaum at slate.com. Rosenbaum, naturally, parades the familiar (again, cliché) idea that Arendt's phrase "the banality of evil" is too dismissive.

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Nuclear Holocaust - Whether We Like it or Not

I'm reading some rather grim reports today. Maybe it's because I'm listening to Sunn O)))'s new album Monoliths and Dimensions. But I can't help be feel a certain need to predict, based on the information cobbled between these two articles and the readings from Michael Hardt and Judith Butler, that there will be a world government-type entity within the next 100 years. That there would be such a government, in itself is not grim for me. What I find grim is that there might not be one - because there might not be the need (given the inadequate human population) for any kind of State at all.

I started reading Wired's wonderful blog, Danger Room, and came across this teaser article from this month's issue Inside the Apocalyptic Soviet Doomsday Machine.

The above article tells us a bit about Dead Hand, technically it's called Perimeter, a zombie nuclear retaliation machine developed by the Soviet Union to destroy the United States after the U.S. has attacked. How will the zombie system know when to strike? Hopefully none of that fails; they keep upgrading the system so hopefully it's overcome the limits of 1984's computing technology and it's not being run on an Apple IIe or something.

Then, from the discussion below the above article I was pointed toward Daniel Ellsberg's article at Truthdig "A Hundred Holocausts: An Insider’s Window Into U.S. Nuclear Policy"

From Ellsbueg's article I noted several interesting lines that reminded me of the discussion we'd been having in Judith Butler's class. Specifically I'm thinking of the question she shares with Arendt, what kind of Law can we have when immorality is the morality of the land? What kind of crime can we charge Eichmann with when there is no legal precedent for the new kind of person that marks our contemporary moment?

As we can see from the recent scholarship on the unaccounted-for fires that accompany nuclear blasts, we can expect all life to be destroyed within about 60 square miles of the blast itself. From Whole World on Fire (Cornell, 2004)

View Larger Map

all of this on fire.

Let's juxtapose some quotes from Ellsberg and Arendt:

I started reading Wired's wonderful blog, Danger Room, and came across this teaser article from this month's issue Inside the Apocalyptic Soviet Doomsday Machine.

The above article tells us a bit about Dead Hand, technically it's called Perimeter, a zombie nuclear retaliation machine developed by the Soviet Union to destroy the United States after the U.S. has attacked. How will the zombie system know when to strike? Hopefully none of that fails; they keep upgrading the system so hopefully it's overcome the limits of 1984's computing technology and it's not being run on an Apple IIe or something.

Then, from the discussion below the above article I was pointed toward Daniel Ellsberg's article at Truthdig "A Hundred Holocausts: An Insider’s Window Into U.S. Nuclear Policy"

From Ellsbueg's article I noted several interesting lines that reminded me of the discussion we'd been having in Judith Butler's class. Specifically I'm thinking of the question she shares with Arendt, what kind of Law can we have when immorality is the morality of the land? What kind of crime can we charge Eichmann with when there is no legal precedent for the new kind of person that marks our contemporary moment?

To be sure, Americans, and U.S. Air Force planners in particular, were the only people in the world who believed that they had won a war by bombing, and, particularly in Japan, by bombing civilians. In World War II and for years afterward, there were only two air forces in the world, the British and American, that could so much as hope to do that.Ellsberg's pointing to a problem that reminds me of Arendt's questions about Eichmann and genocide in her Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship:

How can you think, and even more important in our context, how can you judge without holding on to preconceived standards, norms, and general rules under which the particular cases and instances can be subsumed? Or to put it differently, what happens to the human faculty of judgement when it is faced with occurrences that spell the breakdown of all customary standards and hence are unprecedented in the sense that they are not foreseen in the general rules, not even as exceptions from such rules? (26)Although the idea that the US Air Force might decide that not only is it acceptable to implement and enact on plans to destroy civillian non-combatants as a key to victory is not immediately related to the Arendt questions above (I mean, if we're already accepting that war is a solution to problems why not), the following statements by Ellsberg that proceed from his thinking do begin to resonate with Arendt and her Eichmann project.

I knew personally many of the American planners, though apparently—from the fatality chart—not quite as well as I had thought. What was frightening was precisely that I knew they were not evil, in any ordinary, or extraordinary, sense. They were ordinary Americans, capable, conscientious and patriotic. I was sure they were not different, surely not worse, than the people in Russia who were doing the same work, or the people who would sit at the same desks in later U.S. administrations. I liked most of the planners and analysts I knew. Not only the physicists at RAND who designed bombs and the economists who speculated on strategy (like me), but the colonels who worked on these very plans, whom I consulted with during the workday and drank beer with in the evenings.The chart to which he refers above is the chart that he will be handing to the President that states that at a minimum 325 million people would be killed in the USSR and China were the U.S. to enact general nuclear war in 1961. But he recognized that the Joint Chiefs of Staff were not including the collateral deaths that would have to be included due to nuclear fall out. The reply from the Joint Chiefs of Staff was 600 million dead. One hundred Holocausts within six months in the northern hemisphere. But that was back when we had the less powerful nuclear war heads of 1961, and so few!

That chart set me the problem, which I have worked on for nearly half a century, of understanding my fellow humans—us, I don’t separate myself—in the light of this real potential for self-destruction of our species and of most others. Looking not only at the last eight years but at the steady failure in the two decades since the ending of the Cold War to reverse course or to eliminate this potential, it is hard for me to avoid concluding that this potential is more likely than not to be realized in the long run.

As we can see from the recent scholarship on the unaccounted-for fires that accompany nuclear blasts, we can expect all life to be destroyed within about 60 square miles of the blast itself. From Whole World on Fire (Cornell, 2004)

Average air temperatures in the areas on fire after the attack would be well above the boiling point of water, winds generated by the fire would be hurricane force, and the fire would burn everywhere at this intensity for three to six hours. Even after the fire burned out, street pavement would be so hot that even tracked vehicles could not pass over it for days, and buried unburned material from collapsed buildings could burst into flames if exposed to air even weeks after the fire.To help you understand what 60 square miles looks like, here's a map of the city of Atlanta. Everything within the the Perimeter (the ring that marks I-285) will be on fire and producing hurricane-force winds for three to six hours. That means you can probably include all the suburbs on fire within the first day, especially in tree-city.

Those who sought shelter in basements of strongly constructed buildings could be poisoned by carbon monoxide seeping in or killed by the oven-like conditions. Those who sought to escape through the streets would be incinerated by the hurricane-force winds laden with firebrands and flames. Even those who could find shelter in lower-level subbasements of massive buildings would likely die of eventual heat prostration, poisoning from fire-generated gases or lack of water. The fire would eliminate all life in the fire zone [40-65 square miles is not unreasonable to expect]. (35-36)

View Larger Map

all of this on fire.

Let's juxtapose some quotes from Ellsberg and Arendt:

"What was frightening was precisely that I knew they were not evil, in any ordinary, or extraordinary, sense. They were ordinary Americans, capable, conscientious and patriotic." Ellsberg

"The indictment implied not only that he [Eichmann] had acted on purpose, which he did not deny, but out of base motives and in full knowledge of the criminal nature of his deeds. As for the base motives, he was perfectly sure that he was not what he called an innerer Schweinehund, a dirty bastard in the depths of his heart; and as for his conscience, he remembered perfectly well that he would have had a bad conscience only if he had not done what he had been ordered to do....Their case rested on the assumption that the defendant, like all 'normal persons,' must have been aware of the criminal nature of his acts, and Eichmann was indeed normal insofar as he was 'no exception within the Nazi regime.' However, under the conditions of the Third Reich only 'exceptions' could be expected to react 'normally.' This simple truth of the matter created a dilemma for the judges which they could neither resolve nor escape."I just can't help but feel that Arendt's consideration of the anomaly of Eichmann must be extended to the U.S. and the former Soviet Union. I think that the world, whenever possible, will seek out a central authority and I believe the nuclear crisis will bring that central authority to power. The world will cry out for it, assuming that the majority of the world's life were to survive this crisis.

Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 25-6.

Monday, September 21, 2009

Judith Butler Day 6

NOTE TO FACEBOOK VIEWERS: to view any of the clips you'll need to visit the actual blog. Scroll to the bottom and click "View Original Post"

Judith Butler taught a class entitled ETHICS AND POLITICS AFTER THE SUBJECT. The first half of the classes were focused on Hannah Arendt: performativity, politics, political theory (sovereignty, zionism), "Questions of Judgement."

NOTE: As with all my notes from the EGS, there will likely be mistakes because I did not record the lectures, I made notes as they spoke, so I am perhaps interpreting what they are saying as I am writing.

Precarious Life (2005)

I wrote Frames of War (2009) because I felt that I had left hanging the question of life. I want a different idea of ontology and sociality; something less idealistic than Arendt's plurality.

There are agnostic tensions in relationality, we would have to think about other living organisms.

When a shared position of precariousness is not reciprocated, those populations can become losable, this is what happens in war.

The dispossession of being, as we are unable to choose with whom we cohabitate is the condition necessary for us to act in precarity

My own position doesn't tell us how to punish the war criminal or how to respond to Israel-Palestine; this does, however, give us ways of thinking about war and conflict that inform us of who loses in these conflicts - we both do.

[END OF SECTION]

We adjourn briefly and then reconvene with Giorgio Agamben and Judith Butler in conversation

Judith Butler taught a class entitled ETHICS AND POLITICS AFTER THE SUBJECT. The first half of the classes were focused on Hannah Arendt: performativity, politics, political theory (sovereignty, zionism), "Questions of Judgement."

NOTE: As with all my notes from the EGS, there will likely be mistakes because I did not record the lectures, I made notes as they spoke, so I am perhaps interpreting what they are saying as I am writing.

Precarious Life (2005)

I wrote Frames of War (2009) because I felt that I had left hanging the question of life. I want a different idea of ontology and sociality; something less idealistic than Arendt's plurality.

- How could a person exercise judgement in thorough constraint? If you think critique is based on locality, then living under totalizing conditions would seem to suggest no way of critique - Arendt sought to find a way out of this

- Is plurality compatible with these notions of judgement? Something more than normativity is at work here - modes of cohabitation seems to be a lens through which to see more.

- Plurality is an unchosen way of life; nonetheless, there are obligations to the social, cohabitation is a given.

- "Men must actualize their sheer passive givenness of life..." "in order to make it articulate in the face of suffering, this givenness - calling forward our being." The Human Condition

- It seems to me we are up against others we never chose, vice versa; this produces a range of emotion

- Arendt says we must work in concert, but how does this free acting in concert depend on the unfreedom of cohabitation, with those we never chose nor choose?

- There is a constitutive unfreedom that defines us. The earth belongs to us all.

- If you agree you can't choose with whom to share the earth, you can choose more localized cohabitations, we might employ Heidegger's distinction between earth and world.

- It's peculiar: she distinguishes between power and violence

- Arendt's singular thatness, perhaps in Responsibility and Judgement

- the Copenhagen lecture - she talks about "persona"

There are agnostic tensions in relationality, we would have to think about other living organisms.

- Plurality would have to be also thought as a material interdependence such that exposure and hunger are problematic

- These are not pursued by Arendt

- She makes a distinction between public and private that seems to facilitate this noninclusion, thus it's difficult to think politically and materially interdependent

- It's one thing to apprehend the precariousness of the other, but then we must apply this to material conditions

- A bodily ontology would rethink exposure, social belonging, work, interdependence, etc.

- We must resist giving over to Liberal notions of identity and assume interbeing

- To be a body is to be exposed to being crafted, it emerges in a set of relations and exposed to the configurations of these relations

- The inhibition of freedom as the condition of freedom

- The body's barrier to the Other and the world is at the skin, we are always exposed to the world

- In order to exist as desiring beings we must address the conditions of bodily interdependency - Arendt rules this out as being in the private sphere

When a shared position of precariousness is not reciprocated, those populations can become losable, this is what happens in war.

- Durability is fought for in this unequal distribution of precarity and

- the precarity of life among "the enemy" is a call used to shore-up and insist upon the impermeability of the group

The dispossession of being, as we are unable to choose with whom we cohabitate is the condition necessary for us to act in precarity

My own position doesn't tell us how to punish the war criminal or how to respond to Israel-Palestine; this does, however, give us ways of thinking about war and conflict that inform us of who loses in these conflicts - we both do.

[END OF SECTION]

We adjourn briefly and then reconvene with Giorgio Agamben and Judith Butler in conversation

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Judith Butler Day 5

NOTE TO FACEBOOK VIEWERS: to view any of the clips you'll need to visit the actual blog. Scroll to the bottom and click "View Original Post"

Judith Butler taught a class entitled ETHICS AND POLITICS AFTER THE SUBJECT. The first half of the classes were focused on Hannah Arendt: performativity, politics, political theory (sovereignty, zionism), "Questions of Judgement."

NOTE: As with all my notes from the EGS, there will likely be mistakes because I did not record the lectures, I made notes as they spoke, so I am perhaps interpreting what they are saying as I am writing.

The first half of this class we discuss binationalism and Israel; the second half we discuss transgender and psychoanalysis things.

Why does she work on both of these issues?

She also recommends the film Arna's Children:

Note to Self: Robert Frost's "Mending Wall" as a non-linguistic action which demonstrates how we might live adjacently?

Gender

Who counts as real or who has recognizable gender? This is a question that shows ontology changes the way in which we recognize the world.

Melancholia

We're recommended to read Freud's "Mourning and Melancholia"

[END OF CLASS]

Judith Butler taught a class entitled ETHICS AND POLITICS AFTER THE SUBJECT. The first half of the classes were focused on Hannah Arendt: performativity, politics, political theory (sovereignty, zionism), "Questions of Judgement."

NOTE: As with all my notes from the EGS, there will likely be mistakes because I did not record the lectures, I made notes as they spoke, so I am perhaps interpreting what they are saying as I am writing.

The first half of this class we discuss binationalism and Israel; the second half we discuss transgender and psychoanalysis things.

Why does she work on both of these issues?

- modes of address, how we are called, what are the names by which we are interpellated - "Am I that name?" a reference to Sojourner Truth, Fanon asks, "Am I a [white] man?"

- My son just calls me JB and I'm fine with whatever, which is lame, I guess.

- It is from the basis of my Jewish education I came to be vocally critical of Israel, which got me called a lot of names.

- This chills intellectual inquiry.

- I feel my work has been concerned with implicit and explicit censorship - Hannah Arendt was called a lot of names

- There are questions of fracturous co-habitation and community, which is part of the thinking in transgender thinking.

- What would it mean to take this Levinasian idea, to take it to a place even he was unwilling to go? (we are referred to Jonathon N. Boyarin)

- Benjamin seems to have an idea of the messianic (youtube) that is not progressive and is sporadic and ...(temporary?)

- Scholem separates from Arendt and Benjamin by claiming that Messianism is progressive and based on an ancient claim that this is situated in time. See Raluca Eddon

- The Question of Zion, Jacqueline Rose - she blames Messianism stating the catastrophe of Israel is recreated so as to establish this Messianic narrative; but, she fails to account for the different forms of Messianism.

- Arendt is said to have no love for the Jewish people, to which she replied, "No, I have no love for nations, I love persons."

- Physis and not nomos (social order) - to say, "I am not a Jew," is to say, "I am a Man," is to talk about phusis, the natural order. It is a given and something to be thankful for.

- To understand her position we have to understand what she is doing with the nation-state: they inevitably create exiles and refugees for those that are not part of the nation

- A nation for Jews of Jews is problematic for Arendt because its similarities to Nazism. In her mind, when you base a state on a homogeneous population it is problematic because this leads to another Holocaust.

- This critique does not come from only outside of Israel (how subversive!) we can look to Idith Zertal (although mainly in French) and Adi Ophir

- she becomes concerned with the stateless in the late-40s early 50s; perhaps this is due to her own forced exile.

- we are recommended to read Edward Said's "Freud and the Non-European"

- By focusing on the problematic of the diaspora, Said takes up the idea of the political diaspora

- Arendt does call for home and belonging, but these can never be the basis of a polity b/c a plurality cannot have one part that is exemplary of the whole.

- To have a polity is to accept the unchosen stranger, perhaps an echo of Levinas

- Federated binationalism seems to be an experiment in critiquing sovereignty and perhaps federations resemble/result in smaller forms of self-determinism.

- Statelessness is a condition where there is an extreme distribution of power among a few

- This is not a metaphysical state, but metaphysics is under siege

She also recommends the film Arna's Children:

Note to Self: Robert Frost's "Mending Wall" as a non-linguistic action which demonstrates how we might live adjacently?

Gender

Who counts as real or who has recognizable gender? This is a question that shows ontology changes the way in which we recognize the world.

- it's an Hegelian problem of recognition

- Whose lives are mournable? grew from this. There is an unequal distribution of grieve-ability and this is largely dependent upon the dominant framing among the media.

- Antigone's claim was that she wanted to bury her brother in public.

- Plato wanted to ban poets because the public would grieve voluptuously, they would fatten on grief.

- Here Butler tells us a great story about attending an GLBT poetry slam in San Francisco during which one poet, who was working towards becoming male from female, recited a poem that ended with the lines "fuck the DSM-IV, and fuck you, Judith Butler." This has been told before, apparently.

- The poet rejected "Butler" (the interpellation) for being a representation of gender non-fixity, which does not meet her needs for being understood as a fixed-gender person.

- It is an unfortunate problem to have to address one that we no longer wish to address because it is often necessary to tell that person - we have this need to live within a name.

- We might think of Kate Borstein as a closet Deleuzean, where the transformation never ends, which brings her closer to my thinking.

- Can we think of transexuality without reinforcing sociological/psychological categories in our call for recognition?

Melancholia

We're recommended to read Freud's "Mourning and Melancholia"

- Mourning - where loss is accepted

- Melancholia - where loss is not allowed. Self-laceration is a way of preserving the other in our bodies. We are angry at the lost and strike-out at them, now housed in ourselves. This is the basis of Freud's idea of the superego.

- what would it take to disengage this formation?

- we must forget and let go of that other

- At a cultural level, where there are those that can't be mourned, we get a culturally-induced melancholia

- such that we don't have the vocabulary to describe the loss we have.

[END OF CLASS]

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

Symposium: Judith Butler and Giorgio Agamben

Judith Butler and Giorgio Agamben combined a session of their classes to discuss ideas about THE PROBLEM OF THE SUBJECT AND ACTION.

NOTE: As with all my notes from the EGS, there will likely be mistakes because I did not record the lectures, I made notes as they spoke, so I am perhaps interpreting what they are saying as I am writing.

Judith Butler (JB): We're going to jump from topic to topic

Giorgio Agamben (GA): this peculiar liturgy of the trial. connect the office of Eichmann - who spoke Officialese - see the film The Specialist (trailer at the link). He presents himself as just a man of the law, there is the counterpart in the film (the prosecutor). The problem became the bureaucracy.

JB: Arendt refers to the trial as a spectacle, would this correspond to liturgy

GA: ...It's embarrassing to see the inability of the Law here: the calls for papers, this call to the bureaucracy.

JB: The mystery of the Law, its administrative tragedy in its ridiculousness, is there a legitimate Law and an illegitimate Law? Or do they both participate in liturgy?

GA: There is this book The Mystery of the Process (???). The truth of the Law is the process. The normativity is not the essence, the process itself is the truth of Law. To distinguish in the process might, after Schmidt, be legality and legitimacy. This is hypothetical, the Nazi laws were legal but not legitimate. Today this is not easy to do, Arendt takes a position outside Law, from a moral position.

JB: I'm wondering if we could talk about Kafka for a minute. The way you're discussing Law suggests there is no grounding outside of jurisprudence, no moral call. Perhaps we could talk of a Kafkan law?

GA: But there is no House of Law, it shifts, sometimes it's in the laundry room...

JB: But there is a resonance between what you are saying, that Law is only maintained due to a faith in the liturgical process.

GA: Kafka's process shows what he thinks. Law is a process, it is never clear if he's been accused. Law is something in which man's subjectivity gets involved. It is K that goes to the House of Judgement, the Priest tells him the Law wants nothing from him. The novel starts with calumny, from the Latin calumnia, the Roman process would put the accused on a list, thus the falsely accused was a great problem. Those that are found guilty of calumnia are branded with the letter "K" on their foreheads (read this discussion!). Each man calumniates himself, thus K goes to the House of Law.

JB: Doesn't one's name falsely name and carry an ineffable guilt from another time? In The Illuminations Arendt writes about the transmission, a sickness of transmission - there is no chain of command in the trial, there are these exoteric ways in which Law is transmitted. K carries him in ways that we cannot trace. Is there a difference in Jewish Law and liturgical Law? Is there more than one model of the transmission of the Law?

GA: Benjamin says that ours is a transmission that has nothing more to transmit. We are this moment now: we have a transmission but it has nothing to tell us.

JB: Are there many?

GA: There are many, yes. In Kafka the Law rebels against itself so that the stories of the Talmud are vying for transmission of the Law.

JB: Is Justice recoverable or is it lost?

GA: Law is the door of Justice, when we study Law but don't apply it we enter the House of Law.

Tim Giman-Sevcik (PhD student): Do we accept the death penalty?

GA: I do not support any form of punishment at all. I recognize that people will be punished, but how can we be pro-Punishment?

JB: I do not support capital punishment and I think this would be true for Eichmann. Maybe one has to work with these passions, for seeing destruction, and sober-up from this intoxicated destructiveness that exists. This is a Nietzschean problem.

---------------------------------------

JB: I do believe we need accountability, but how to use the juridical as the primary organ for sensing aggrievements and that suffering can somehow be equated to a punishment against the guilty. Perhaps there is no subject which can be found guilty for certain crimes. Perhaps some kinds of happiness that courts can't give us.

GA: The Coming Insurrection was written by friends of mine and it is difficult to talk about. We should be concerned that now every political action outside of Parliament is equated with terrorism.

NOTE: As with all my notes from the EGS, there will likely be mistakes because I did not record the lectures, I made notes as they spoke, so I am perhaps interpreting what they are saying as I am writing.

Judith Butler (JB): We're going to jump from topic to topic

Giorgio Agamben (GA): this peculiar liturgy of the trial. connect the office of Eichmann - who spoke Officialese - see the film The Specialist (trailer at the link). He presents himself as just a man of the law, there is the counterpart in the film (the prosecutor). The problem became the bureaucracy.

JB: Arendt refers to the trial as a spectacle, would this correspond to liturgy

GA: ...It's embarrassing to see the inability of the Law here: the calls for papers, this call to the bureaucracy.

JB: The mystery of the Law, its administrative tragedy in its ridiculousness, is there a legitimate Law and an illegitimate Law? Or do they both participate in liturgy?

GA: There is this book The Mystery of the Process (???). The truth of the Law is the process. The normativity is not the essence, the process itself is the truth of Law. To distinguish in the process might, after Schmidt, be legality and legitimacy. This is hypothetical, the Nazi laws were legal but not legitimate. Today this is not easy to do, Arendt takes a position outside Law, from a moral position.

JB: I'm wondering if we could talk about Kafka for a minute. The way you're discussing Law suggests there is no grounding outside of jurisprudence, no moral call. Perhaps we could talk of a Kafkan law?

GA: But there is no House of Law, it shifts, sometimes it's in the laundry room...

JB: But there is a resonance between what you are saying, that Law is only maintained due to a faith in the liturgical process.

GA: Kafka's process shows what he thinks. Law is a process, it is never clear if he's been accused. Law is something in which man's subjectivity gets involved. It is K that goes to the House of Judgement, the Priest tells him the Law wants nothing from him. The novel starts with calumny, from the Latin calumnia, the Roman process would put the accused on a list, thus the falsely accused was a great problem. Those that are found guilty of calumnia are branded with the letter "K" on their foreheads (read this discussion!). Each man calumniates himself, thus K goes to the House of Law.

JB: Doesn't one's name falsely name and carry an ineffable guilt from another time? In The Illuminations Arendt writes about the transmission, a sickness of transmission - there is no chain of command in the trial, there are these exoteric ways in which Law is transmitted. K carries him in ways that we cannot trace. Is there a difference in Jewish Law and liturgical Law? Is there more than one model of the transmission of the Law?

GA: Benjamin says that ours is a transmission that has nothing more to transmit. We are this moment now: we have a transmission but it has nothing to tell us.

JB: Are there many?

GA: There are many, yes. In Kafka the Law rebels against itself so that the stories of the Talmud are vying for transmission of the Law.

JB: Is Justice recoverable or is it lost?

GA: Law is the door of Justice, when we study Law but don't apply it we enter the House of Law.

Tim Giman-Sevcik (PhD student): Do we accept the death penalty?

GA: I do not support any form of punishment at all. I recognize that people will be punished, but how can we be pro-Punishment?

JB: I do not support capital punishment and I think this would be true for Eichmann. Maybe one has to work with these passions, for seeing destruction, and sober-up from this intoxicated destructiveness that exists. This is a Nietzschean problem.

- Naming should be subjected to the same liabilities of any other transmission

---------------------------------------

JB: I do believe we need accountability, but how to use the juridical as the primary organ for sensing aggrievements and that suffering can somehow be equated to a punishment against the guilty. Perhaps there is no subject which can be found guilty for certain crimes. Perhaps some kinds of happiness that courts can't give us.

- If we were to base our politics on the sovereign decider, we would have a Schmidtian disaster.

GA: The Coming Insurrection was written by friends of mine and it is difficult to talk about. We should be concerned that now every political action outside of Parliament is equated with terrorism.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Judith Butler Evening Lecture

Judith Butler gave an evening lecture that I think was entitled HOW TO KEEP COMPANY WITH ONESELF.

NOTE: As with all my notes from the EGS, there will likely be mistakes because I did not record the lectures, I made notes as they spoke, so I am perhaps interpreting what they are saying as I am writing.

Thinking itself depends on politics and ethics in Arendt's philosophy, thus we understand her charge against Eichmann.

Thinking is keeping company with oneself and it reconstitutes the self over and again.

Acting is keeping company with others and this reconstitutes the plurality over and again.

Freedom is not the exercise of the individual, but acting in concert and belonging. Rights do not belong to an individual but humans as social animals.

Thinking is an individual's acting, how do we resolve this tension?

A crime against humanity is not a crime against an individual and an individual is also not solely responsible for crimes against humanity.

NOTE: As with all my notes from the EGS, there will likely be mistakes because I did not record the lectures, I made notes as they spoke, so I am perhaps interpreting what they are saying as I am writing.

Thinking itself depends on politics and ethics in Arendt's philosophy, thus we understand her charge against Eichmann.

- Is this a naive claim or that she has a highly normative way of thinking?

- She thought the trial failed to try the man or the crime, that it was a pretense for the founding of the nation of Israel

- His was a failure to critique positive law and that his not-thinking when he thought he was thinking was a failure because he failed to recognize that thinking necessarily implicates us in a plurality and in sociality.

- Were Eichmann to have reformulated the categorical imperative such that it required everyone to serve the Führer, Arendt's rejoineder to Eichmann would still be: every man is a legislator upon acting

- She thought that the trial failed to recognize that a new kind of person had come to be: what kind of person can this be in a world where we no longer think?

- Eichmann was not a sadist, not a murderer, but only following the rules.

- His crime was against the plurality and so the plurality judges him.

- The meaning of plurality is unclear here but acts as an antidote to nationalism. The plurality, by definition, cannot know or fit within the nation.

- It is the use of "we" in the final judgement of Eichmann (in the Epilogue), that pronoun ("we") does the work of realizing the aspirations of those that would seek an alternative to the dangers of nationalism.

- She obeys no law in sentencing Eichmann to death, she calls for law that is not seeking precedent as we must oppose bad laws when bad laws are the laws of the land

- When she speaks she is not speaking for those the Nazis tried to destroy and also not as a judge but as a call for differentiation

- She references to forms of plurality: the self and the broader sociality

- The self that thinks is folded over and dyadic and maintains the last trace of company

- I find myself populated precisely when I am isolated: conscience and consciousness are the relationship to itself

- This split is the precondition for thinking to occur.

- What Arendt seems to be providing is a philosophical anthropology which features a nonvisible dialogue between the self and then to the plurality of mankind

- This dialogue has a performative dimension, action is never a single action but a concerted action

- What follows if one fails to follow this thinking (plurality)? The result is that they cannot speak.

Thinking is keeping company with oneself and it reconstitutes the self over and again.

Acting is keeping company with others and this reconstitutes the plurality over and again.

- The "I" is constituted or brought forth by language, itself a social action.

- It seems that solitary thinking presupposes the relating to others and action requires responding with others

- Thinking itself seems to presuppose that we will be acting with others

Freedom is not the exercise of the individual, but acting in concert and belonging. Rights do not belong to an individual but humans as social animals.

Thinking is an individual's acting, how do we resolve this tension?

A crime against humanity is not a crime against an individual and an individual is also not solely responsible for crimes against humanity.

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

Colloquium: Judith Butler, Larry Rickels, and Avital Ronell

NOTE TO FACEBOOK VIEWERS: to view any of the clips you'll need to visit the actual blog. Scroll to the bottom and click "View Original Post"

Today's class was a special joint session with Avital Ronell's morning class (those of us in Larry Rickels' morning class also had Judith Butler in the afternoon). In this, perhaps, symposium is another fold into what it means to be together and to live together. We will be discussing Heidegger's What Is Thinking?, some Melanie Klein, and viewing an interview (Zur Person, a German TV program from 1964) with Hannah Arendt while discussing her ideas on judgement.

We begin with Judith Butler:

Butler offers us some light translation from the above video:

How are we to understand these phantom diacritical marks (fluttering her eyes, blowing her cigarette smoke into Gaus' face) in her talk about not being welcome into the community of (male) philosophers?

Here we might have a psychoanalytic reading of Arendt's relationship with Heidegger within this interview using the figure of loneliness, Melanie Klein's On the Sense of Loneliness to suggest where we can detect the relationship to Heidegger

Arendt discusses being alone in her essay Some Questions of Moral Philosophy

ALSO: Cato quote at end of the above section: "Never am I more active than when I do nothing, never am I less alone than when I am by myself." In contrast to the 圣人 shengren (sage) who does nothing and in doing nothing leaves nothing undone.

Melanie Klein peruses loneliness as the inevitable break-out of the therapeutic practice; the need to mitigate between hate and love is at the center of integration

Butler

Avital mentioned Arendt not feeling welcome - this is the expression of a wound. Perhaps she might be anticipating a wounding, thus wounding herself so as to control the wounding.

Derrida refers to Lot's offering to the strangers when discussing hospitality

Kant situates us so:

Both Heidegger and Arendt state that they are not philosophers, they are both upset with philosophy

Adorno is the figure in Germany in 1964 (during the Zur Person interview), Arendt at this time is editing Benjamin's Illuminations where she says Adorno was Benjamin's best student [Ronell here quips, "And then Arendt put her cigarette out!"]

Ronell

Zen-like practice so as to maintain a relationship with the self; an ethical injunction

NOTE TO SELF: if we're to follow this thought out we should consider ningen 人間 (the betweenness of humanity)

Butler

Ronell

One is defanged as a philosopher at points - what does one take recourse to in an emergency? What is a person vs. personality?

Rickels

There is the ability now, through mass technologization, to self-administer the shock so as to survive

NOTE TO SELF: overcoming by undergoing the work of being together - as transformative

Ronell

from What Is Thinking? (54) "[N]o thinker can be overcome by our refuting him and stacking up around him a literature of refutation. What a thinker has thought can be mastered only if we refer everything in his thought that is still unthought back to its originary truth."

Rickels

It's as though her training is immersed in the political as finitude

Ronell

from Some Questions of Moral Philosophy

Speech as radical self-generation:

Today's class was a special joint session with Avital Ronell's morning class (those of us in Larry Rickels' morning class also had Judith Butler in the afternoon). In this, perhaps, symposium is another fold into what it means to be together and to live together. We will be discussing Heidegger's What Is Thinking?, some Melanie Klein, and viewing an interview (Zur Person, a German TV program from 1964) with Hannah Arendt while discussing her ideas on judgement.

We begin with Judith Butler:

Butler offers us some light translation from the above video:

- "Political philosophy - which I avoid - there is always a tension between man as thinking being and man as acting being. Natural philosophy does not allow this."

- Arendt is introduced by Günter Gaus as a major thinker, but she says she doesn't feel like she is a philosopher and points out that she is not accepted as such.

- The private domain has no speech, it is an arena in which bodies labor; defined by repetitive and transient actions

- To have speech properly means it must be done in the public domain

- These distinctions are based on the Greek polis but they are nonexclusionary; the public depends on the private to exist and yet this dependency is never theorized as a political issue because the public contains the private.

- Arendt states in the interview, "Heidegger is a philosopher (and solitary), I am a political theorist (and public), thus I do something different," this seems like some sort of gossipy speculation

- There is a shift in her interview where she goes from talking about philosophy to talking about giving commands

- She must the interpellation of philosopher if she is to protect her femininity; perhaps one day there will be a philosopher that does not give commands

- Is she becoming feminine in this move or is she becoming hyper-masculine by becoming a political theorist which takes the public sphere as central, a sphere from which women have historically been excluded (a woman's place being in the home, a private domain)?

- Eichmann's failure to think was a failure not only to maintain an inner dialogue but also a failure to think of somebody else.

How are we to understand these phantom diacritical marks (fluttering her eyes, blowing her cigarette smoke into Gaus' face) in her talk about not being welcome into the community of (male) philosophers?

- Heidegger says that TV is an expression of his form of solitary thinking

- Arendt says we are more dependent upon our silence, a partner for thinking, a call she is having that is difficult

- that consciousness is more than being with myself alone but has something to do with being responsible

- Levinas says you are never responsible enough, Derrida says that we must stand against what is unethical, even if alone, even if alone with a friend

Here we might have a psychoanalytic reading of Arendt's relationship with Heidegger within this interview using the figure of loneliness, Melanie Klein's On the Sense of Loneliness to suggest where we can detect the relationship to Heidegger

Arendt discusses being alone in her essay Some Questions of Moral Philosophy

(100) I mention these various forms of being alone, or the various ways in which human singularity articulates and actualizes itself, because it is so very easy to confuse them, not only because we tend to be sloppy and unconcerned with distinctions, but also because we they invariably and almost unnoticeably change into one another. The concern with the self as the ultimate standard of moral conduct exists of course only in solitude. Its demonstrable validity is found in the general formula "It is better to suffer wrong than to do wrong," which, as we saw, rests on the insight that it is better to be at odds with the whole world than, being one, to be at odds with myself. This validity can therefore be maintained only for man insofar as he is a thinking being, needing himself for company for the sake of the thought process.Earlier in the same essay Arendt discusses the distinctions between solitude and isolation:

(98) Solitude means that though alone, I am together with somebody (myself, that is). It means that I am two-in-one, whereas loneliness as well as isolation do not know this kind of schism, this inner dichotomy in which I can ask questions of myself and receive answers. Solitude and its corresponding activity, which is thinking, can be interrupted either by somebody else addressing me or, like every other activity, by doing something else, or by sheer exhaustion. In any of these cases, the two that I was in thought become one again. If somebody addresses me, I must now talk to him, and not to myself, and in talking to him, I change. [...] Because this one who I now am is without company, I may reach out for company of others - people, books, music - and if they fail me or if I am unable to establish contact with them, I am overcome by boredom and loneliness. For this I do not have to be alone: I can be very bored and very lonely in the midst of a crowd, but not in actual solitude, that is, in my own company, or together with a friend, in the sense of another self. That is why it is much harder to bear being alone in a crowd than in solitude - as Meister Eckhart once remarked.Isolation, on the other hand:

(99) [O]ccurs when I am neither together with myself nor in the company of others but concerned with things in the world. Isolation can be the natural condition for all kinds of work where I am so concentrated on what I am doing that the presence of others, including myself, can only disturb me. Such work may be productive, the actual fabrication of some new object, but need not be so.... Isolation can also occur as a negative phenomenon....[I]t is the enforced leisure of the politician, or rather of the man who is himself a citizen but has lost contact with his fellow citizens. Isolation in this second negative sense can be borne only if it is transformed into solitude, and every one who is acquainted with Latin literature will know how the Romans, in contrast to the Greeks, discovered solitude and with it philosophy as a way of life in the enforced leisure which accompanies removal from public affairs.NOTE TO SELF: Does Lynch's talk about Jay-Z's hegemony becomes strained if we start discussing the solitude of hiphop? Is there solitude in hiphop? It seems that the only successful rappers to "leave the game" were Biggie and 2Pac, and clearly these aren't tenable exit strategies.

ALSO: Cato quote at end of the above section: "Never am I more active than when I do nothing, never am I less alone than when I am by myself." In contrast to the 圣人 shengren (sage) who does nothing and in doing nothing leaves nothing undone.

Melanie Klein peruses loneliness as the inevitable break-out of the therapeutic practice; the need to mitigate between hate and love is at the center of integration

- While lack of integration has its pains, the process of integration (in analysis) brings its own pains

- Klein valorizes idealization and seeks to preserve the cleavage between the good and the bad - not the good preserved - this is a Nietzschean moment that separates her from Freud

- Idealization is already marked by Klein as disposable, as integration is never permanent, the glamor of idealization (as the Good Object) is gone, though, at some point.

- When it leaves, it leaves us with the loneliness of transference

(104) ...Socratic morality is politically relevant only in times of crisis and that the self as the ultimate criterion of moral conduct is politically a kind of emergency measure. And this implies that the invocation of allegedly moral principles for matters of everyday conduct is usually a fraud; we hardly need experience to tell us that the narrow moralists who constantly appeal to higher moral principles and fixed standards are usually the first to adhere to whatever fixed standards they are offered....We catch a whiff of Heidegger just prior to the above quote:

(104) This ambiguity, that the same act will make good men better and bad men worse, was once alluded to by Nietzsche who complained of having been misunderstood by a woman: "She told me that she had no morality - and I thought that she had, like myself, a more severe morality." The misunderstanding is common although the reproach in this particular case (Lou Andreas Salome) was far off the mark.Heidegger must have been the Good Object at one point: the two-in-one continues to threaten the none-in-one.

Butler

Avital mentioned Arendt not feeling welcome - this is the expression of a wound. Perhaps she might be anticipating a wounding, thus wounding herself so as to control the wounding.

- Did she not feel Heidegger was appreciative enough?

- Who is this other with whom I must think?

- Do I preserve the Other by a melancholic sense of loss?

- this cleavage (that Larry mentioned) as the precondition for thought?

Derrida refers to Lot's offering to the strangers when discussing hospitality

Kant situates us so:

- we are hosting a guest and the cops come looking for the guest - do we tell the truth and give the guest over to them or do we lie?

- Kant says give the guest over

- Arendt says Kant did not have an ear fir the possibility of the horror that can occur in his truth-telling world

- That which is mourned, homecomings, are toward the future; this loneliness is in this sense a two-in-one

- She is performing an excentric half, calls forward to the core of Heidegger's What Is Thinking? so as to aberrate it

Both Heidegger and Arendt state that they are not philosophers, they are both upset with philosophy

- Heidegger is now a thinker

- The will to listening and obeying are both intimately connected for Heidegger as was pointed out by Nietzsche -

(What Is Called Thinking?, 48) "You just wait - I'll teach you what we call obedience!" a mother might say to her boy who won't come home. Does she promise him a definition of obedience? No. Or is she going to give him a lecture? No again, if she is a proper mother. Rather, she will convey to him what obedience is. Or better, the other way around: she will bring him to obey. Her success will be more lasting the less she scolds him; it will be easier, the more directly she can get him to listen - not just condescend to listen, but listen in such a way that he can no longer stop wanting to do it. And why? Because his ears have been opened and he now can hear what is in accord with his nature. Learning, then, cannot be brought about by scolding.

- What does he who is taught by the proper mother hear?

- The son who is not present - is Heidegger calling Nietzsche home? not to keep him but to lose him?

- The mother of muses, remembrance and memory, is first invoked in What Is Called Thinking?

Adorno is the figure in Germany in 1964 (during the Zur Person interview), Arendt at this time is editing Benjamin's Illuminations where she says Adorno was Benjamin's best student [Ronell here quips, "And then Arendt put her cigarette out!"]

Ronell

Zen-like practice so as to maintain a relationship with the self; an ethical injunction

NOTE TO SELF: if we're to follow this thought out we should consider ningen 人間 (the betweenness of humanity)

Butler

(99) If somebody addresses me, I must now talk to him, and not to myself, and in talking to him, I change. I become one, possessing of course self-awareness, that is, consciousness, but no longer fully and articulately in possession of myself.There is a dynamic movement between me and the Other in thinking - I can only be within the context between us.

Ronell

One is defanged as a philosopher at points - what does one take recourse to in an emergency? What is a person vs. personality?

Rickels

There is the ability now, through mass technologization, to self-administer the shock so as to survive

NOTE TO SELF: overcoming by undergoing the work of being together - as transformative

Ronell

from What Is Thinking? (54) "[N]o thinker can be overcome by our refuting him and stacking up around him a literature of refutation. What a thinker has thought can be mastered only if we refer everything in his thought that is still unthought back to its originary truth."

Rickels

It's as though her training is immersed in the political as finitude

Ronell

from Some Questions of Moral Philosophy

(95) The greatest evildoers are those who don't remember because they have never given thought to the matter, and without remembrance, nothing can hold them back. For human beings, thinking of past matters means moving in the dimension of depth, striking roots and thus stabilizing themselves, so as not to be swept away by whatever may occur - the Zeitgeist or History or simple temptation. The greatest evil is not radical, it has no roots, and because it has no roots it has no limitations, it can go to unthinkable extremes and sweep over the whole world.Butler

Speech as radical self-generation:

(SQMP, 95) Taking our cue from Socrates' justification of his moral proposition, we may now say that in this process of thought in which I actualize the specifically human difference of speech, I explicitly constitute myself a person, and I shall remain one to the extent that I am capable of such constitution ever again and anew. If this is what we commonly call personality, and it has nothing to do with gifts and intelligence, it is the simple, almost automatic result of thoughtfullness. To put it another way, in granting pardon, it is the person not the crime that is forgiven; in rootless evil there is no person left whom one could ever forgive.Heidegger sounded the call:

(WICT? 49) ...[A] man who teaches must at times grow noisy. In fact, he may have to scream and scream, although the aim is to make his students learn so quiet a thing as thinking. Nietzsche, most quiet and shiest of men, knew of this necessity. He endured the agony of having to scream. In a decade when the world at large still knew nothing of world wars, when faith in "progress" was virtually the religion of the civilized peoples and nations, Nietzsche screamed out into the world: "The wasteland grows..." [...] What was once the scream "The wasteland grows...," now threatens to turn into chatter. The threat of this perversion is part of what gives us food for thought. The threat is that perhaps this most thoughtful thought will today, and still more tomorrow, become suddenly no more than a platitude, and as platitude spread and circulate. This fashion of talking platitudes is at work in that endless profusion of books describing the state of the world today. They describe what its by nature is indescribable, because it lends itself to being thought about only in a thinking that is a kind of appeal, a call - and therefore must at times become a scream. Script easily smothers the scream, especially if the script exhausts itself in description, and aims to keep men's imagination busy by supplying it constantly with new matter. The burden of thought is swallowed up in the written script, unless the writing is capable of remaining, even in the script itself, a progress of thinking, a way.[END OF CLASS]

Monday, September 7, 2009

Judith Butler, Day 3

Judith Butler taught a class entitled ETHICS AND POLITICS AFTER THE SUBJECT. The first half of the classes were focused on Hannah Arendt: performativity, politics, political theory (sovereignty, zionism), "Questions of Judgement."

Some business before we being today's class: Tomorrow we will be discussing with Larry Rickels and Avital Ronell some of Arendt's moral philosophy and some of Heidegger's essay What Is Thinking? We'll talk a bit about gender as well by way of an interview Arendt did in 1964 - she seems to be suggesting that philosophy is a masculine activity.

There is a textual theatre at play in this book. At one point Arendt scripts for the judge and at another point she's using her own voice to ventriloquize and then dropping that again to allow the script to continue

It's true: she draws parallels between Israel and Nazi Germany, however, Nazi Germany had certain forms of bureaucratic administration and control such that political judgement was not possible.

Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship from Responsibility and Judgment

[END OF CLASS]

Some business before we being today's class: Tomorrow we will be discussing with Larry Rickels and Avital Ronell some of Arendt's moral philosophy and some of Heidegger's essay What Is Thinking? We'll talk a bit about gender as well by way of an interview Arendt did in 1964 - she seems to be suggesting that philosophy is a masculine activity.

(EiJ, 277) Foremost among the larger issues at stake in the Eichmann trial was the assumption current in all modern legal systems that intent to do wrong is necessary for the commission of a crime. On nothing, perhaps, has civilized jurisprudence prided itself more than on this taking into account of the subjective factor. Where this intent is absent, where, for whatever reasons, even reasons of moral insanity, the ability to distinguish between right and wrong is impaired, we feel no crime has been committed. We refuse, and consider as barbaric, the propositions "that a great crime offends nature, so that the very earth cries out for vengeance; that evil violates a natural harmony which only retribution can restore; that a wronged collectivity owes a duty to the moral order to punish the criminal" (Yosal Rogat). And yet I think it is undeniable that it was precisely on the ground of these long-forgotten propositions that Eichmann was brought to justice to begin with, and that they were, in fact, the supreme justification for the death penalty.She's arguing here for a distinction between justice (as vengeance in the archaic sense by bringing him to trial and issuing a death sentence) and judgement

- It seems she should be understood as opposing vengeance as justice and advocating that with the Eichmann trial we confront the unprecedented nature of the crime and then develop a notion of justice based not on vengeance but on judgement

- She called it, not murder but, administrative murder - what needs to appear here is something not enclosed but capable of being spoken of in the pursuit of justice based on judgement

- Even if it were the case that the Israeli court said that "We must be seen by all to be exacting our vengeance..." this is one way we could interpret this summoning of voices during the Epilogue to EiJ. If we were to understand it thus, we could then see that what was really occurring was that administrative noise was being overcoded on top of an archaic pursuit of vengeance called justice in the Eichmann case as an act of nation building.

- But there is this voicing in the text... Arendt as judge, an equivocation of what's being said? She's ventriloquizing the judge.

There is a textual theatre at play in this book. At one point Arendt scripts for the judge and at another point she's using her own voice to ventriloquize and then dropping that again to allow the script to continue

It's true: she draws parallels between Israel and Nazi Germany, however, Nazi Germany had certain forms of bureaucratic administration and control such that political judgement was not possible.

- She refuses that this is a German problem, nor is it only a Jewish problem - it's not limited to this or that nation; this is an administrative problem endemic within Modernity

- A broader problem of technical administration, a transnational problem

- The Little Picture and Critique of Instrumental Reason - these are some arguments from the Frankfurt School

Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship from Responsibility and Judgment

(26-7) To return to my personal reflections on who should be qualified to discuss such matters: is it those who have standards and norms which do not fit the experienc, or those who have nothing to fall back upon but their experience, an experience, moreover, unpatterned by preconceived concepts? How can you think, and even more important in our context, how can you judge without holding on to preconceived standards, norms, and general rules under which the particular cases and instances can be subsumed? Or to put it differently, what happens to the human faculty of judgement when it is faced with occurrences that spell the breakdown of all customary standards and hence are unprecedented in the sense that they are not foreseen in the general rules, not even as exceptions from such rules? A valid answer to these questions would have to start with an analysis of the still very mysterious nature of human judgement, of what can and what it cannot achieve. For only if we assume that there exists a human faculty which enables us to judge rationally without being carried away by either emotion or self-interest, and which at the same time functions spontaneously, that is to say, is not bound by standards and rules under which particular cases are simply subsumed, but on the contrary, produces its own principles by virtue of the judging activity itself; only under this assumption can we risk ourselves on this very slippery moral ground with some hope of finding a firm footing.Foucault and I (Butler) would be turning in our graves at the suggestion that one might judge in this manner: based on pre-existing norms and not being carried away by emotion and self-interest...!

(41) They [the Nazis] acted under conditions in which every moral act was illegal and every legal act was a crime. Hence, the rather optimistic view of human nature, which speaks so clearly from the verdict not only of the judges in the Jerusalem trial but of all postwar trials, presupposes an independent human faculty, unsupported by law and public opinion, that judges in full spontaneity every deed and intent anew whenever the occasion arises. Perhaps we do possess such a faculty and are lawgivers, every single one of us, whenever we act: but this was not the opinion of the judges. Despite all the rhetoric, they meant hardly more than that a feeling for such things has been inbred in us for so many centuries that it could not suddenly have been lost. And this, I think, is very doubtful in view of the evidence we possess, and also in view of the fact that year in, year out, one "unlawful" order followed the other, all of them not haphazardly demanding just any crimes that were unconnected with each other, but building up with utter consistency and care the so-called new order. This "new order" was exactly what it said it was -- not only gruesomely novel, but also and above all, an order.Why can't we appeal to a deep-seated morality latent within the individual? (Mengzi did) Why spontaneity? It seems to have something to do with freedom.

- If this is judgement, then who is entitled to judgement? We don't say, "I will judge freely and so not be held accountable to Law."

- There seems to be some form of sovereignty present here - to judge is to judge freely, it is the action of freedom in judgement. This is from Kant's Third Critique - all of us free and smart

- Arendt looks to Kant to understand freedom, Foucault also did this in his What Is Enlightenment? he sees Kant as Prussia

- The whole problem of culture is that when the law is criminal it is criminal to be moral

(34) For the simple truth of the matter is that only those who withdrew from public life altogether, who refused political responsibility of any sort, could avoid becoming implicated in crimes, that is, could avoid legal and moral responsibility. In the tumultuous discussion of moral issues which has been going on ever since the defeat of Nazi Germany, and the disclosure of the total complicity in crimes of all ranks of official society, that is of the total collapse of normal moral standards....She's trying to escape relativism, that we are all responsible, she doesn't think that external circumstances should dictate.

[END OF CLASS]

Friday, September 4, 2009

Judith Butler, Day 2

Judith Butler taught a class entitled ETHICS AND POLITICS AFTER THE SUBJECT. The first half of the classes were focused on Hannah Arendt: performativity, politics, political theory (sovereignty, zionism), "Questions of Judgement." The last two classes were shared with Avital Ronell, Larry Rickels, and Giorgio Agamben.

Butler studied with Gadamer at the University of Heidelberg (where he was the successor to Jaspers, who moved to Switzerland in 1948). She earned a PhD in philosophy, but feels the term is problematic for her; she prefers interdisciplinarity.

This interdisciplinarity is shared with Hannah Arendt who was a: journalist, philosopher (a student of Heidegger along with Gadamer), public diplomat, and historian. We must accept that philosophy takes place in many places, journalism (as Eichmann in Jerusalem shows) is one of those places.

Responsibility and Judgement was written after EiJ, and in the wake of the anger that arose from the publication from it.

Judgement

What sort of action is this exactly? How'd she get from Eichmann to Kant's Third Critique?

Judgement is more in line with poiesis, a manner of making, than it is an instrument

The kind of judgement we are to make is dependent upon the context in which we encounter the unprecedented

If a radically-new condition arises, spontaneity is implicated in judging

There has to be a moral basis for condemning genocide and it cannot rest upon existing law

The Israeli courts didn't do a good job judging because Eichmann was tried in many ways as a substitute for all Nazis: is the trial of an individual man the right place to put on trial all those that supported Nazism?

Classically understood: if Eichmann is criminal, there must be evidence of criminal intent; all the psychologists find that he's "normal."

Maybe the victims shouldn't be the judges of Eichmann - perhaps, if this is a crime against humanity then an international court should sit in judgement?

For the judges-

Butler studied with Gadamer at the University of Heidelberg (where he was the successor to Jaspers, who moved to Switzerland in 1948). She earned a PhD in philosophy, but feels the term is problematic for her; she prefers interdisciplinarity.

This interdisciplinarity is shared with Hannah Arendt who was a: journalist, philosopher (a student of Heidegger along with Gadamer), public diplomat, and historian. We must accept that philosophy takes place in many places, journalism (as Eichmann in Jerusalem shows) is one of those places.

Responsibility and Judgement was written after EiJ, and in the wake of the anger that arose from the publication from it.

- This book is a collection of essays on moral theory that are responses to the Eichmann trial and the criticisms she received from her reporting on the trial

- Her last book (incomplete) Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy deals with the question of how one judges without precedent

- We know that Eichmann failed to think, so this has something to do with judging.

- What are the abilities to judge when society is ruled by coercion?

- Arendt faults Eichmann for failing to perform freedom

- he remains responsible for what he did, one does not need to be a thinking being in order to be responsible

- his failure to think (given there is a normativity to thinking) is part of his crime (his crime is in part his failure to think)

- Thinking has a duality: I think in the company of myself (a position not dissimilar to Bakhtin); thinking implies the presence of others - alterity cannot be located in a singular other, this is a plural other

- the status of sovereignty - here we have an appeal to sovereign mind, but also calls for plurality

- the relation between thinking and action (judgement is action) - thinking seems to require sociality

Judgement

What sort of action is this exactly? How'd she get from Eichmann to Kant's Third Critique?

- Arendt seems upset that Eichmann tried to invoke Kant in his defense (Eichmann stated he tried to live his life according to Kant's categorical imperative) and thus was not guilty for the murder of millions

- The object of beauty imposes upon the viewer such that the viewer must form structures by which to judge that which is being viewed